Q: Was surrealism something you wanted to do/you aimed at?

A: Not really. I love the Surrealists, and I Love…I think…Magritte the best…and I love them thinking about dreams. I love the name Surreal, and I love how they would go for meaning in random acts, and I love the way they would combine almost the opposites and make the human mind…make them work together.—David Lynch

Since dreams often reveal the true nature of things, it was important to me as a composer to create acoustic images to avoid being dependent on imagery.

…

The unspoken becomes a nightmare; waiting and false hopes take root in every skin particle if open questions are silenced. For if you know precisely what to expect you can be calmer: that, however, was denied to both Fred and Pete. Equality in a relationship, however, is only possible if you try to take each other seriously and to get the other involved. Therefore, the seemingly neutral silence becomes an unbearable demonstration of power over another person. This is what "Lost Highway" is about.—Olga Neuwirth

Olga Neuwirth (b.1968), Lost Highway (2002/3)

This week we are looking at an audio recording of a musical theater adaptation of a film. Your experience with the recording as a standalone work will vary based on multiple factors, including familiarity with the original film and its director’s approach to filmmaking; an understanding of the staging, production design, and even the life of the composer; and your familiarity and level of comfort with various forms of surrealist art. Finding an onramp to this particular highway could be challenging if these are new frontiers for you. If these are roads well traveled, then buckle up. Objective truth? Power plays? Identity fracturing and trauma? Toxic Masculinity? Artistic jealousy and weakness? Confidence tricksters? A simple heist? Noir Femme Fatales and their dupes? Fascist attitudes towards rule breaking? Free Jazz? These are some things one finds along the lost highway, but not all. How you deal with these things is entirely up to you. For Fred Madison, our principal character, life has become that of an ouroboros forever on the run. I will not attempt to tell you the “correct” interpretation of Lost Highway. Instead, I will discuss three different scenes from the movie and the theater piece and look at how they contrast and complement each other. I will also try to explain some of my affinity for the work and why I find this type of artistic expression and its various manifestations so valuable.

Solo (Film 4:45-21:05)

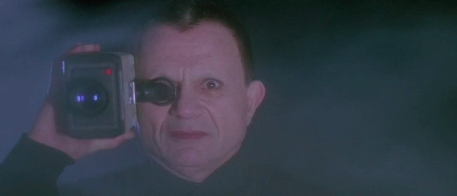

Fred Madison is a musician. In the film, he is a tenor saxophonist. In Olga Neuwirth’s adaptation, he is a trumpet player. Why the switch? Well, before Neuwirth was a successful composer, she was a young aspiring professional trumpet player. An auto accident left her with a severely injured jaw at age 15 that redefined her identity. Having never interviewed Neuwirth personally, that’s as far as I dare go. Only she knows how connected she feels to the character of Fred Madison, perhaps not at all. Potential empathies abound, though. In the film, Madison is a sexually frustrated musician with a beautiful wife he has trouble satisfying in bed. She supports his life as a musician but doesn’t always accompany him to his gigs, preferring to stay home, read, and sleep. Madison’s multiple frustrations splinter into suspicions, jealousy, and eventually _______. As any musician in a committed relationship must learn, your passions as a musician are your own and should never be transferred onto your spouse. They have their own passions and interests, and to expect them to share yours with complete devotion could be considered a form of abuse. Attending a world premiere once a year is one thing, but coming to the club regularly to hear a three-hour set of white-hot free jazz? Lines must be drawn. To expect otherwise invites evil into the bedroom, or at least a wide-eyed, heavily motivated personification of objective truth with a steadycam-quality handheld. Neuwirth has been in the game long enough to know these things, and so have I. Fred? Apparently, not so much. This is one example of toxic masculinity portrayed in Lost Highway, although one could argue that it’s more a case of poisonous artistry.

Events lead to the fracturing of Madison's psyche, represented in the film when Fred physically transforms into Pete Dayton, a highly sought-after auto mechanic with "the best ears in the business." He can listen to an engine and diagnose any problem. Because of this, he is Mr. Eddie's Man!

2. Rules (Film 1:00:37-1:03:48)

Mr. Eddie gets what he wants - cars, women, money - and he does not tolerate tailgating (film version) or smoking when there's a No Smoking sign posted (theater version). In the film, Mr. Eddie forces a tailgater off the road during a test drive and starts to pistol whip him. It's much easier to show this characteristic on stage using a No-Smoking sign instead of having to stage an elaborate car chase production number along the winding roads of California. It’s also interesting to note that Lynch is (was?) an unabashed smoker. Neuwirth pumps up the absurdity in the musical version by writing a demanding vocal performance for Mr. Eddie that includes register jumps, scream speech, and other careening vocal gestures. The film version is so over the top that it plays somewhat comedically (buckle up) as Mr. Eddie lays out all of the statistics regarding tailgating to his victim as the witnesses to his behavior, including Pete/Fred, are horrified.

When Mr. Eddie returns to the shop to drop off his car for repairs, a woman is in the car with him. It is the same woman who had been married to Fred, except she is now a platinum blonde. Pete is transfixed, instantly obsessed, and wonders if he is seeing things when Alice makes her first appearance. In the film, this scene plays out as Lou Reed’s cover of The Drifters’ This Magic Moment plays in the foreground. For her version of this scene, Neuwirth strips away the vocals, keeps the harmonic progression, and distorts the music with tuning adjustments and pitch bends, adding a hallucinogenic sheen to the proceedings. Neuwirth then follows the first appearance of Alice with an instrumental interlude that includes the free jazz trumpet solo from earlier in the piece. In Lynch’s film, the solo can be heard playing on a shop radio being enjoyed by another Lynchian doppelganger, Eraserhead himself, Jack Nance. All of this suggests that Fred Madison is still with us, just beneath Pete’s exterior, and that realities are starting to converge.

At least the Mystery Man tried, or did he goad with his False Mirrors? Either way, neither Fred nor Pete seem capable of self-awareness and will remain trapped in a cycle of destruction and manipulation until one of them decides they’ve BOTH had enough and it’s time to take the next exit.

Look! Is that a billboard for a Transcendental Meditation retreat? Just 50 miles ahead on the left. Take the Rancho Rosa exit and turn around.